Racial disparities in endometriosis diagnosis: A conversation

TL/DR: It takes an average of 8-12 years to obtain a diagnosis of endometriosis, and studies show that there are differences in how the diagnosis is made depending on the race of the patient — even with other factors controlled. Racism, not race, drives health disparities. Here’s what you need to know:

Why black and hispanic individuals are less likely to be diagnosed with endometriosis

Endometriosis is a complex disease that often makes itself known through painful periods, irregular bleeding, and an assortment of other symptoms that vary from person to person. 1 Left untreated, it’s associated with serious health issues (such as infertility and endometrial cancer). And it’s still not entirely understood: Most of today’s endometriosis treatment options are centered around pain relief and symptom management; as of right now, there is no universally accepted cure.

As research continues, however, some concerning statistics have been brought to the forefront – including this: Historical data shows that endometriosis is often differentially diagnosed based on race.

In other words, diagnoses are made more or less frequently based on the race/ethnicity of the patient, even when there is no intrinsic reason underlying such a difference. This suggests that the reason for differences has more to do with bias in the medical system and healthcare disparities, than with race itself.

One recent study found that Asian women were more likely than white women to be diagnosed with endometriosis. Black and Hispanic women, on the other hand, were less likely than white women to be diagnosed with endometriosis. 2

Yet when looking at other reproductive health conditions such as uterine fibroids or infertility, this trend is flipped on its head. The exact figures shift with every emerging study, but current estimates round out that Black women are, on average, three times more likely to have fibroids, and two times more likely to experience infertility compared to white women. 3 4

Why is endometriosis the outlier? It’s a complicated conversation, and while we can’t delve into everything there is to discuss about racial disparities in endometriosis diagnosis, we’ll introduce some of the themes that are most important to joining the conversation and advocating for change.

Let’s dive in:

Healthcare disparities vs. Health disparities

To fully understand what’s happening with endometriosis, let’s first define a couple of science research-y terms: healthcare disparities and health disparities. They sound similar, but they mean two totally different things.

Healthcare disparities refers to how healthcare is distributed among different populations.

Remember, “healthcare” means different things for different people (it could be an urgent care center, the local pharmacy, your primary care provider, or a major hospital à la Grey’s Anatomy) – and all of them are valid. The role of healthcare providers is to meet you wherever you are in your health journey.

That said, your experience of healthcare will, to an extent, depend upon your unique life experiences (some of which are under your control, others of which are not). Your zip code, your income, your insurance status, and your individual demographics shift the ways in which you experience and have access to healthcare.

The ways in which this differs between populations, or groups of people, is what constitutes healthcare disparities.

Health disparities refers to differences in health outcomes between different populations.

This could mean things like disease burden (i.e. how many people in a certain population experience cardiovascular disease) or even a statistic as specific as the number of people in a certain population that are diagnosed with a specific disease – for example, diabetes.

What do we mean by “population?” In healthcare research, population refers to a group of people that are connected by at least one attribute, whether that be race, ethnicity, gender assignment at birth, immigration status, citizenship status, or level of insurance. It is a way of organizing information to understand who is accessing healthcare, how they are accessing healthcare, and what their health outcomes tend to be.

What goes into an endometriosis diagnosis?

Despite what your high school biology classes may have led you to believe, medicine is both an art and a science. That means medicine isn’t going to be delivered in exactly the same way from one provider to another. However, when it comes to diagnosing a condition, there are a specific set of processes that medical professionals must follow. Let’s take a closer look at how these apply to endometriosis:

First, keep in mind that some conditions are diagnosed by looking at quantitative, objective information. For example, UTIs can be diagnosed via a urine sample, or many STIs with a blood test. 5 6 Other diseases and illnesses, however, are determined via clinical diagnosis, which means that a healthcare provider with expertise in that disease area focuses on (non-quantitative) signs and symptoms in order to make a diagnosis.

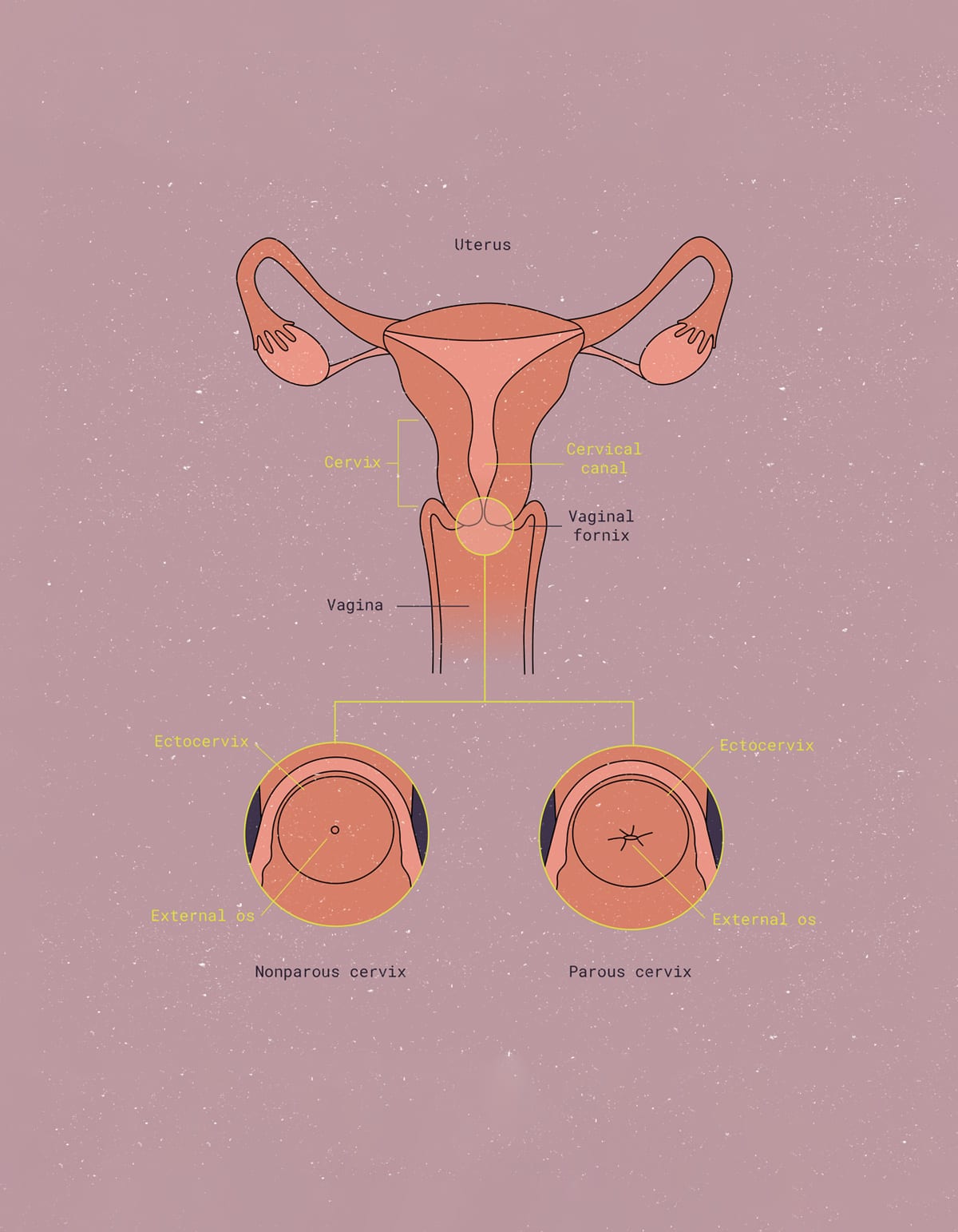

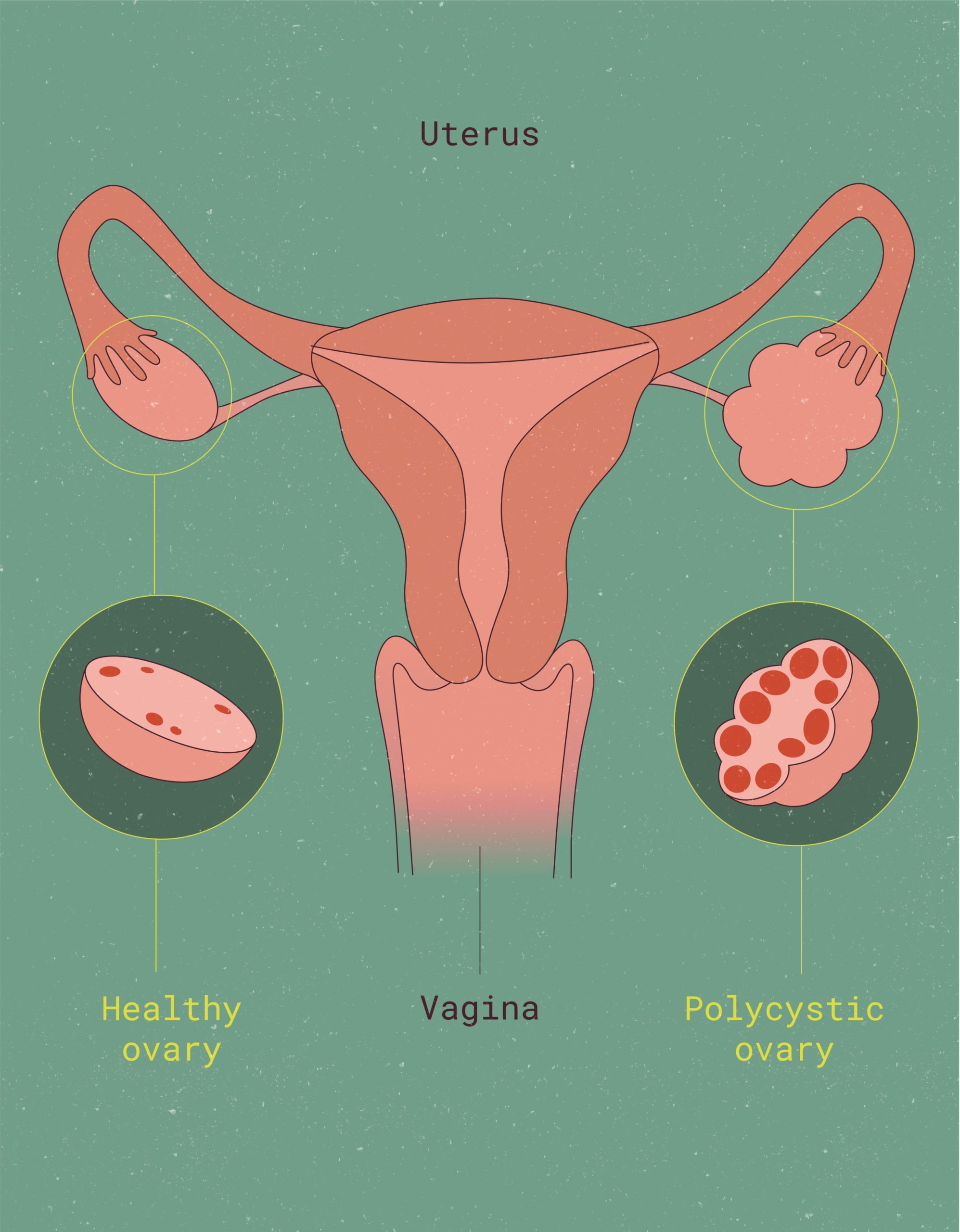

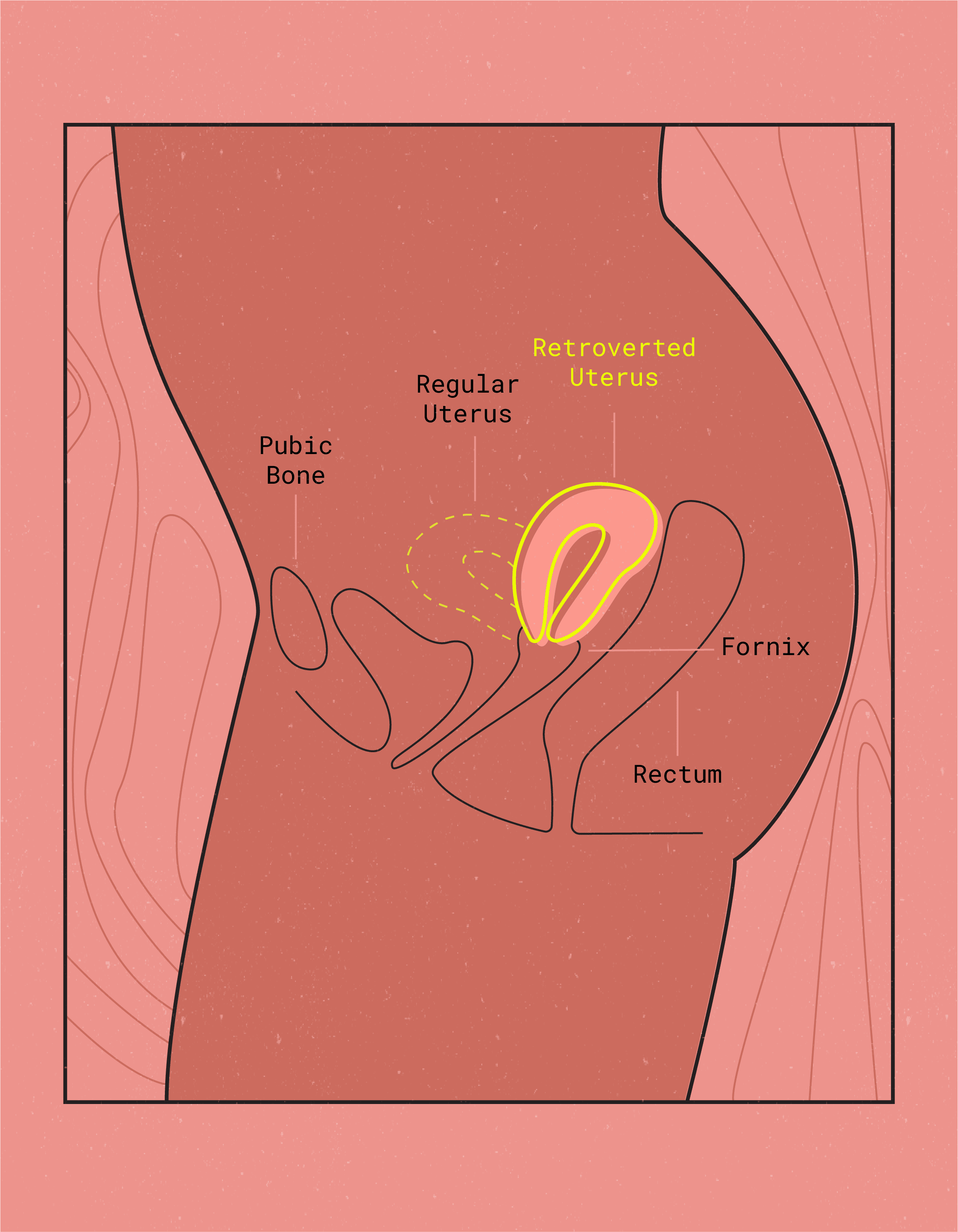

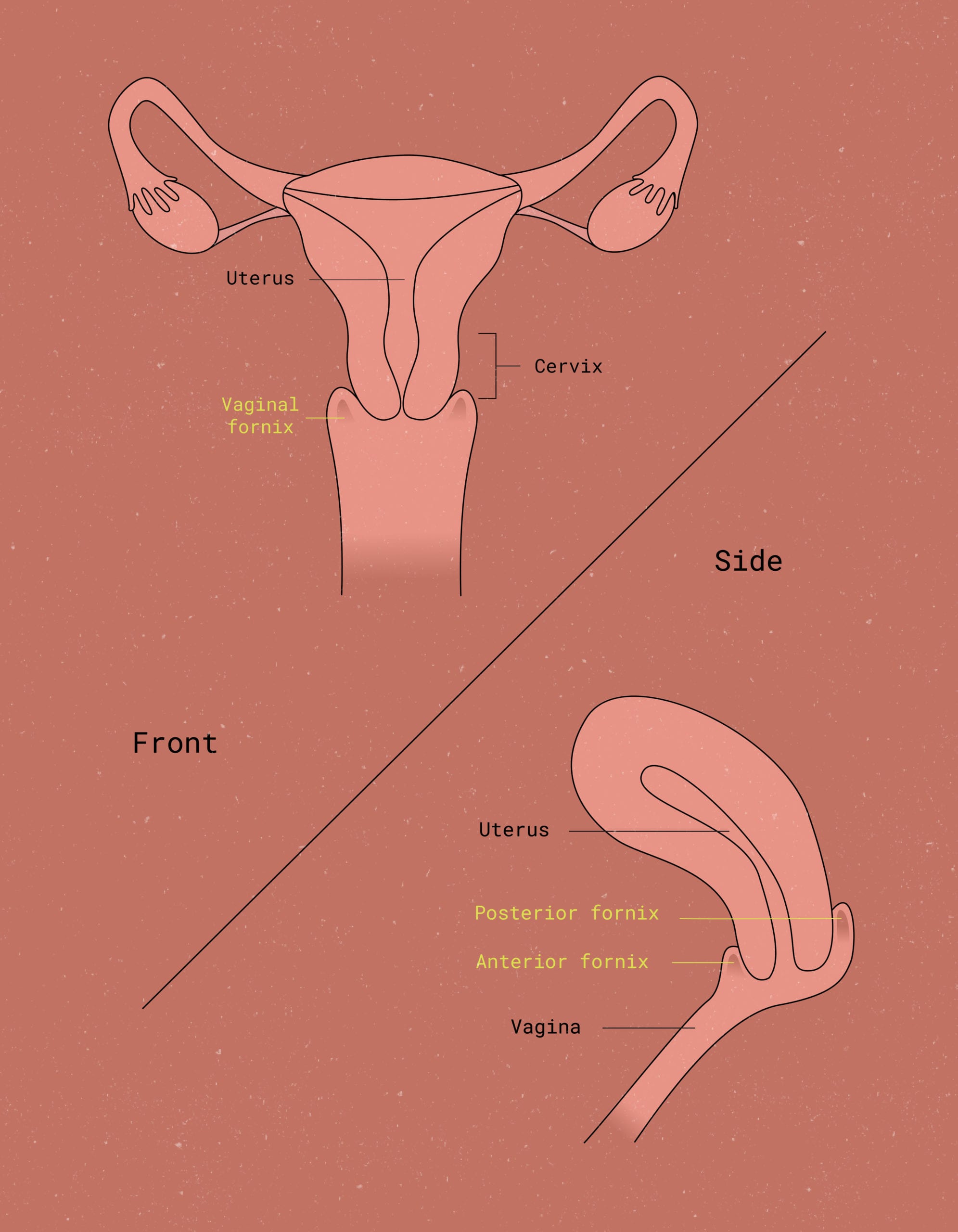

This brings us back to endometriosis. Endometriosis is a fascinating condition because, although there is a somewhat clear definition of what it is (recall from the Flex® Guide to Endometriosis: endometrial-like tissue outside of the uterus), screening and diagnosis is way less straightforward.

Some healthcare providers may screen for endo by looking for what’s called a serum marker (usually the protein CA-125) in a blood test – but this method isn’t perfect, especially when endometriosis is at its early stages. Other providers rely on the patient communicating specific signs and symptoms that match the overall disease pattern, using their own clinical experience as a point of reference.

One of the most definitive diagnostic tools for endometriosis is imaging (such as an ultrasound or MRI) or surgery. While this is the best way to prove that endometrial-like tissue exists outside of the uterus, in other parts of the body, it’s both expensive and time-consuming – which partly explains why many individuals wait an average of 8-12 years for a confirmed diagnosis. 7

And since qualitative, not quantitative, data is what initially brings endo patients in to see their doctors, it’s understandable that endometriosis might not be the first suspect. Early symptoms tend to include painful or heavy periods, pain during sex, and other non-specific symptoms like nausea or vomiting — many of which can happen as a result of other common conditions, and none of which immediately point to endometriosis.

Long story short long: The process for obtaining an endometriosis diagnosis can be time-intensive and expensive, requiring multiple trips to the doctor, tests to rule out other causes, imaging, or even surgical procedures to finally reach a confirmed diagnosis.

Full circle: Understanding racial disparities in reproductive healthcare

Now that you know a little more about how endo is diagnosed, let’s revisit the racial disparities.

Those health outcomes we touched on earlier? Well, they’re the result of complex diagnostic processes, each affected by individual, community, and systems-level factors. And within the US healthcare system, those health outcomes are more heavily tied to race and ethnicity – which means racial inequalities deserve some extra air time within these conversations.

One factor that may help to explain varying diagnosis rates has to do with differences in how providers assess and evaluate pain based on the perceived race or ethnicity of their patient.

It’s well-documented in scientific literature that Black patients are less likely to have their reports of pain believed and acted upon than white patients. 8

For example: One study showed that Black patients were less likely than white patients to be prescribed painkillers in the emergency room, even when they came in with the same exact medical problem (in this case, it was a bone fracture). 9 In this same study, the risk of receiving no painkillers was 66 percent greater for Black patients than white patients. Pain should be treated equally, but it isn’t – and this goes to show that we have a systems-level issue that needs to be addressed.

So, it’s fair to say that there are inequities surrounding medical care in the United States. While explaining why and how this came to be would take hundreds of pages, we can say without a doubt that there’s a difference in how Black and white patients received diagnoses. And these differences may be even more noticeable with a condition like endometriosis, where the initial concern that patients most commonly bring up is pain itself.

There is an urgent need for further research and advocacy to add detail to the many factors contributing to this disparity – and, in particular, to focus on elevating the voices of those that have been historically marginalized by the healthcare system.

Advocacy matters

Now that you have the facts, it’s time to take action. Remember: this is only the beginning of the conversation. Here are some websites and resources to explore for further reading and self-education:

- The American Public Health Association

- Planned Parenthood Federation of America

- Endometriosis Foundation of America

Don’t stop here, though. If you can, try to seek out stories from those who have firsthand experience with endometriosis – especially those who identify as BIPOC (like this personal essay from Tia Mowry). Check out our recent interview with author and endo-warrior Abby Norman, too, and pick up a copy of her book, Ask Me About My Uterus.

Arm yourself with knowledge about endometriosis so that if you, a friend, or a loved one is experiencing something similar, you can feel comfortable speaking up to a healthcare provider. Creating space to share experiences is so important: it helps build a sense of community, spreads knowledge, and provides a support system for those who need it most.

If you’re one of the millions of individuals battling endo, know that you’re not alone – and don’t be afraid to talk about it, whether to your family, friends, or your partner. Consider joining a support group (many providers can point you in the right direction, or join an online forum like MyEndometriosisTeam).

Whoever you are and wherever you are, you deserve compassionate, high-quality reproductive healthcare — and health disparities must be addressed in order to make equitable healthcare a universal goal. So get out there, share the knowledge, and offer some extra support to any endo-warriors in your own life. Speaking up, in both little and big ways, has an impact.

Want to learn more about how to advocate for healthcare equality in endometriosis and beyond? Connect with us on social media or get in touch with us directly at hello@thefornix.com.

This article is informational only and is not offered as medical advice, nor does it substitute for a consultation with your physician. If you have any gynecological/medical concerns or conditions, please consult your physician.

© 2021 The Flex Company. All Rights Reserved.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2019, Jan). Endometriosis. ACOGACOG stands for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (a professional membership organization for obstetrician–gynecologists).. Retrieved from acogACOG stands for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (a professional membership organization for obstetrician–gynecologists)..org/womens-health/faqs/endometriosis[↩]

- Farland, L., & Horne, A. (2019). Disparity in endometriosis diagnoses between racial/ethnic groups. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 126(9), 1115-1116. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15805[↩]

- Stewart EA, Nicholson WK, Bradley L, Borah BJ. The burden of uterine fibroids for African-American women: results of a national survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(10):807-816. doi:10.1089/jwh.2013.4334[↩]

- Wellons MF, Lewis CE, Schwartz SM, et al. Racial differences in self-reported infertility and risk factors for infertility in a cohort of black and white women: the CARDIA Women’s Study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5):1640-1648. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.056[↩]

- Colgan, R. (2011, October 1). Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Uncomplicated Cystitis. American Family Physician. Retrieved from https://www.aafp.org/afp/2011/1001/p771.html.[↩]

- Sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). (2019, October 29) Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/sexually-transmitted-diseases-stds/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20351246[↩]

- Pugsley Z, Ballard K. Management of endometriosis in general practice: the pathway to diagnosis. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57(539):470-476.[↩]

- Hoffman, K. M. (2016, April 19). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. PubMed Central (PMC). Retrieved from ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4843483/[↩]

- Todd, K., Deaton, C., D’Adamo, A., & Goe, L. (2000). Ethnicity and analgesic practice. Ann Emerg Med. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10613935/[↩]