Ask an Ob/Gyn: What causes PCOS?

For PCOS Awareness Month, we’re deep-diving into the recent research

We’re capping off PCOS Awareness Month with a much-requested article: What does the research say about how, exactly, polycystic ovary syndrome develops? Unfortunately, we’ve yet to find the silver bullet that reveals the precise chain of events leading to PCOS—but science has made some definite progress over the past few years.

In case you missed our last blog post on PCOS or need a quick recap, find that article here. Meanwhile, here’s the TL;DR:

PCOS is an endocrine disorder, meaning it’s related to the endocrine system—the system responsible for the production and regulation of hormone levels. PCOS is a bit of a medical enigma because its causes are myriad and it can present with varying symptoms, including cystic acne, missing or infrequent periods, heavy periods, unwanted body hair growth, polycystic ovaries, and insulin resistance.

PCOS is the main cause of anovulatory infertility—a.k.a. infertility caused by lack of ovulation (the ovary doesn’t release eggs). It’s a fairly common condition, affecting up to 15% of AFABAFAB stands for “assigned female at birth.” individuals who are of reproductive age. 1 Besides the physical symptoms of PCOS, it is sometimes also associated with certain mental health disorders, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.2

So… Do we know the exact cause of PCOS?

The exact causes (or causes) of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) remains unclear. This means that there’s no one panacea to treat it.

What we do know, however, is that many people with PCOS have insulin resistance. This may result in higher androgen levels—a key criterion for the diagnosis of PCOS. Secondly, medical research has found that half of those with PCOS are obese, and obesity is known to contribute to high levels of insulin —so the two health conditions can have the effect of working synergistically, and exacerbating PCOS. 3 Lastly? Some believe that PCOS is mostly genetic.

At the end of the day, much research still needs to be conducted before we’ll know with certainty what exact chain of events must take place in the body to lead to PCOS.

PCOS causes, diagnosis and management

While we don’t the exact causes of PCOS, the condition is relatively straightforward when it comes to diagnosis. In most cases, a medical provider will review medical history, any presenting signs of PCOS and common symptoms (like acne, unwanted or excessive hair growth), and perform a pelvic exam.

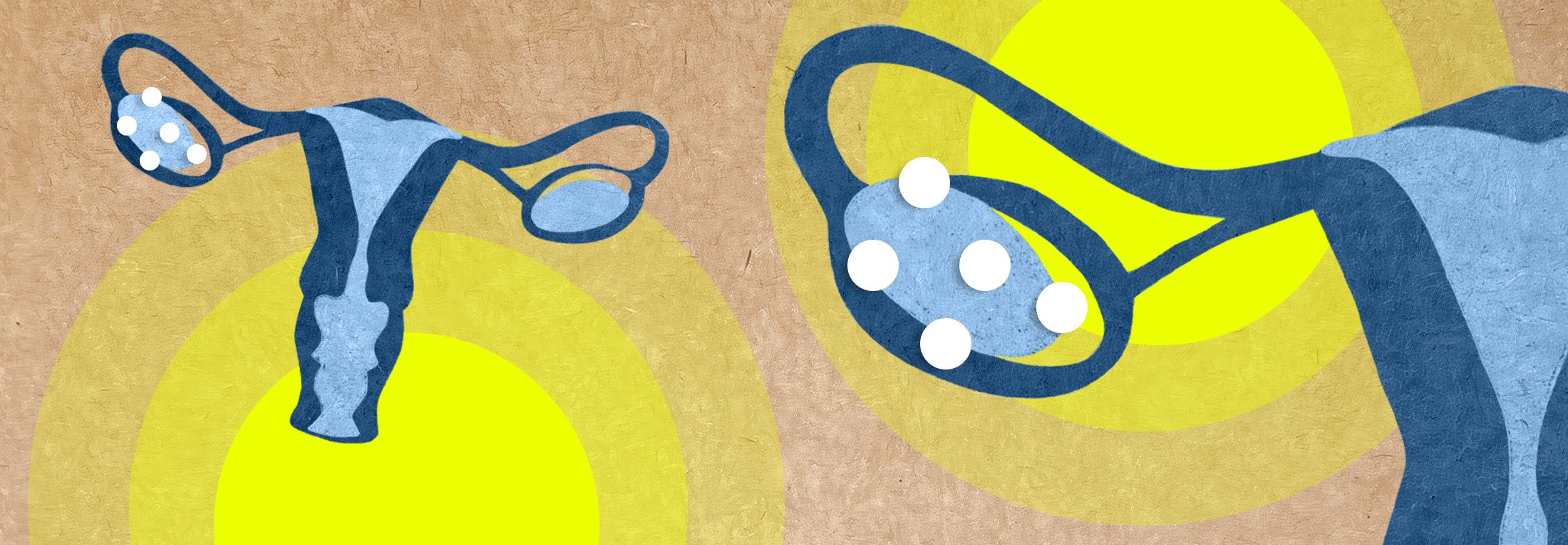

Aside from a physical exam, the doctor can also order an ultrasound to examine the size of the ovaries and cysts. Cysts identified with PCOS are typically not large; in fact, they often present themselves as tiny follicles (12 or more) located peripherally around the ovary. 3 These cysts are small fluid filled sacs that contain immature eggs. Blood tests are also used to check for high levels of a reproductive hormone called androgen and to evaluate blood glucose levels.

Androgens are hormones that play a role in the development of male traits, but they are also present in females. In the context of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, high levels of androgens can lead to symptoms such as acne and excess hair growth. These high levels are often associated with insulin resistance, which contributes to the hormonal imbalance seen in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome.

Managing this condition typically involves a combination of lifestyle changes, medication to regulate hormones and improve insulin sensitivity, and sometimes fertility treatments for those trying to conceive.

Importantly, it’s not necessary to have polycystic ovaries on ultrasound in order to have a diagnosis of PCOS, which makes the name including the word “ovaries” a bit of a misnomer.

There are three different sets of criteria used for a PCOS diagnosis: The National Institutes of Health Criteria, the Rotterdam Criteria, and the Androgen Excess and PCOS Society. Usually, two out of three of the following equals a PCOS diagnosis:

- Hyperandrogenism (a hormonal imbalance where high androgen levels are evidenced, for example, by cystic acne or unwanted hair growth, or as seen on bloodwork)

- Oligomenorrhea (infrequent, irregular periods)

- Polycystic ovaries

Because PCOS affects not only the reproductive organs but various organ systems, management of the condition is most effective when individualized and based on your unique symptoms and fertility goals. Some of the available treatment methods include lifestyle changes, hormonal birth control, laparoscopic ovarian drilling, or various oral medications.

In many cases, patients with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome will be prescribed more than one oral medication. For example, a birth control pill might be recommended to help with hormonal balance and to regulate your menstrual cycle, while spironolactone may be added to treat unwanted hair growth as well as hair loss and cystic acne (it does so by lowering androgen levels). For those with more significant insulin resistance, medications for diabetes—such as metformin, liraglutide, or dapagliflozin—may also be prescribed.

We asked Flex medical advisor Dr. Jane van Dis about what she recommends to patients diagnosed with PCOS:

“PCOS is a multifactorial disease and there isn’t a one-size-fits-all recommendation for each patient,” she explains.

“Having said that, we know that exercise is one of the biggest components in reducing insulin resistance in PCOS. A meta-analysis of 16 studies showed that vigorous exercise was the most likely to reduce insulin resistance. For some women, PCOS is genetic, for others, it can be due to environmental exposures—but regardless, women shouldn’t feel helpless as there are medications that can be helpful, as well as exercise and nutrition components.”

What’s behind this tough-to-pinpoint syndrome? New research looks to insulin resistance, inflammation, and gut microbiota for answers. Some studies show promising findings re: the connection between insulin resistance and the gut microbiome, which is responsible for a diverse range of 1000-1500 species of bacteria.

Let’s take a closer look at these potential Polycystic Ovary Syndrome causes.

Insulin resistance and the gut

A recent study published in the Journal of Ovarian Research showed that gut microbiota composition in patients with PCOS was significantly different compared with those without.4

This study also points out the important link between intestinal flora and factors like obesity and insulin resistance, noting that 50% of patients with PCOS are insulin-resistant. Insulin is a hormone that regulates blood sugar levels by facilitating the uptake of glucose from the bloodstream into cells. Additionally to body weight gain, high blood pressure, among other signs, insulin resistance also plays a role in excess androgen production, leading to hirsutism, acne, and maybe even the development of follicles in the ovary.

As the researchers note, “Insulin resistance is also associated with endotoxemia, chronic inflammatory response, short-chain fatty acids, and bile acid metabolism.” 4 In other words, insulin resistance and chronic inflammation are closely connected.

The study goes on to state, “When intestinal barrier function is impaired, endotoxin produced by intestinal flora enters the blood, [causing] chronic ovarian inflammation and [insulin resistance], hence promoting the occurrence and development of PCOS.”

The authors point to the fact that other recent studies confirm that intestinal flora can regulate the secretion of insulin, resulting in affected androgen metabolism and the development of follicles. Because of the link between intestinal flora, insulin resistance, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome, the authors calls on future studies to look at bacterial profiles and the manipulation of intestinal microbiota as possible treatments for PCOS.

The gut microbiota governs many aspects of health, from metabolism and immunity to pathogen prevention. So, in some ways, it’s not surprising that it might also have an influence on reproductive health.

Another study by the Endocrine Society looked at two groups of obese teenagers—one group with PCOS and one without. All participants had similar BMIs. 5 The study found that the microbiota was significantly altered in adolescents with PCOS, as opposed to adolescents without the syndrome. These findings show us just how important a role gut microbiota play in metabolic disease in adolescents (and perhaps all individuals) with PCOS.

The same study also examined the correlation between insulin levels and the inflammatory response. A state of chronic inflammation affects multiple organs, and particularly affects the insulin receptor and even follicle development.

The authors note, “A leaky gut has been hypothesized to mediate the development of the metabolic syndrome via upregulation of systemic inflammatory response. The systemic inflammatory response has been shown to disrupt various organ functions and could contribute to insulin resistance.” 5

To further examine the relationship between microbiota and PCOS, let’s take a look at a third recent study that examined a group of rats induced with PCOS. 6 The animals displayed similar symptoms to humans with PCOS: Irregular menstrual periods, increasing androgens, and cysts in ovarian tissue.

The PCOS rats were treated with fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) and Lactobacillus, a healthy bacterium that lives in the intestinal tract. The results? Menstrual cycles improved in all PCOS rats, and six of the eight rats in the Lactobacillus transplantation group showed decreasing androgen production.

This indicates that imbalance of gut microbiota is associated with the development of PCOS and that we might benefit from keeping gut considerations front of mind for PCOS treatments. To summarize, as concluded by the authors of the first study we mentioned, “Accumulating evidence has recommended probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics as effective treatment options for PCOS patients.”

Curious about whether probiotics or prebiotics could help your PCOS? It’s always a good idea to consult with your doctor before adding anything new to your diet or supplement regime, but the research looks promising.

Inflammation and PCOS

As with a range of other diseases, researchers found a strong link between PCOS and inflammatory markers. One recent study examined 200 people 18-40 years old with PCOS compared to a healthy control group of 105 people.7 The study aimed to find white blood cell counts and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration in comparison to the control group.

The study concluded that white blood cell counts were significantly higher in PCOS patients. Insulin, glucose, and cholesterol were also elevated. The findings of both increased white blood cells and CRP suggest that chronic low-grade inflammation is present in PCOS.

Because chronic inflammation is a sign of a compromised immune system, we looked to another study that investigated whether PCOS is a risk factor for COVID-19. Interestingly, this study found that patients with PCOS had a 28% increased risk of COVID-19.8

New lifestyle recommendations for PCOS

Because there is still no cure-all treatment for PCOS, it’s important to factor in all of the presenting symptoms when coming up with a treatment plan. Work closely with your healthcare provider or, better yet, reach out to a specialist.

If possible, equip yourself with a multidisciplinary team of providers—for example, a gynecologist, endocrinologist, dermatologist, and dietician (in addition to a primary care physician). Having multiple specialists on board will allow you to tackle PCOS, its symptoms, and its root causes from all angles.

As we mentioned earlier, PCOS left untreated can lead to serious health problems and complications down the road, including (but not limited to) infertility. Dr. Jane adds, “Women with excess levels of estrogen are at increased risk of breast and uterine cancer, and women with excess testosterone are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Both can be deadly, which is why, if you have PCOS, it’s really important to treat it aggressively and watch for any abnormal uterine bleeding.”

This is not to say that a PCOS diagnosis is necessarily life-threatening. Rather, it’s important that you work closely with your healthcare provider to monitor your symptoms and come up with a treatment plan.

Balancing diet and exercise

It’s helpful to remember that insulin resistance can be managed with proper nutrition, especially a diet high in fiber and low in refined sugar. Obesity complicates PCOS and insulin resistance typically makes losing weight more difficult. That’s where the other piece of the puzzle comes into play: Nicholas D. Carricato, MD, says that “moderate exercise can help make your body more sensitive to insulin” and may help with weight loss and PCOS symptom management, as well.9

Official guidelines for PCOS management recommend at least 150 minutes of physical activity per week. 10 This breaks down to only 21 minutes per day which, thankfully, is totally doable! Find something you enjoy doing—whether that’s a team sport, a swim club, or even a local hiking group—to make your workouts feel more like an activity to look forward to and less like a chore.

Dr. Jane recommends adjusting both your diet and exercise routine to maximize the benefits of both: “Diet is always the most important for weight loss,” she notes. “That said, building up muscle mass—like with weight training—is a great way to build exercise endurance, along with increasing baseline metabolism. Cardiovascular exercise is great for heart and vascular health. So, in reality, you shouldn’t leave diet or exercise out.”

For inflammation, “a low-carbohydrate diet will help increase production of short-chain fatty acids which reduces incidence of chronic inflammation.” 4

Other research suggests that high-sugar foods may be one of the inducers of PCOS, reason being that they tend to cause intestinal flora imbalance and trigger chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and production of androgens. With that in mind, try your best to minimize sugary foods in your diet and look for healthier alternatives to things like soda, candy, and baked goods.

Some of our favorite swaps include:

- Soda → Flavored sparkling water

- Candy → Dark chocolate-covered strawberries

- Baked goods → Oatmeal with sliced apples and almond butter

- Ice cream → Homemade chocolate “nice cream” made with (!) avocados

- Fruit juice → Unsweetened iced tea

- Sugary “low fat” yogurt → Plain Greek yogurt with fresh berries

We know—easier said than done, especially when you’re on your period. Working with a dietician or nutritionist will help you find even more healthy swaps so you can improve your eating habits without feeling deprived on your journey to achieving and keeping a healthy weight.

If cost is a limiting factor, keep in mind some nutrition counselors accept sliding scale payment (and there are great online communities where you can find helpful tips and support free of charge). Certain health insurance plans will cover nutritionist or dietician services, as well.

How does PCOS affect pregnancy?

PCOS can lead to , making it harder to conceive. It increases the risk of pregnancy complications, such as gestational diabetes and preeclampsia. Women with PCOS may also have a higher risk of miscarriage and premature birth, requiring careful monitoring and management during pregnancy.

Although one of the most common causes of infertility, women with PCOS can still experience successful pregnancies with proper medical guidance and support. It is essential for women with PCOS to work closely with healthcare providers to manage their condition and maximize their chances of a healthy pregnancy. This may involve lifestyle adjustments, medication management, and monitoring throughout the pregnancy journey.

Here are some other excellent resources for PCOS:

- The PCOS Awareness Association

- The National Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Association

- Information on PCOS from ACOG

- Verity PCOS Self-Help Group

- r/PCOS on Reddit

- @the.hormone.dietician on Instagram

This article is informational only and is not offered as medical advice, nor does it substitute for a consultation with your physician. If you have any gynecological/medical concerns or conditions, please consult your physician.

© 2024 The Flex Company. All Rights Reserved.

- Khan, M. J., Ullah, A., & Basit, S. (2019). Genetic Basis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): Current Perspectives. The Application of Clinical Genetics, 12, 249–260. https://doi.org/10.2147/TACG.S200341[↩]

- Brutocao, C., Zaiem, F., Alsawas, M., Morrow, A. S., Murad, M. H., & Javed, A. (2018). Psychiatric disorders in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endocrine, 62(2), 318–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-018-1692-3[↩]

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/polycystic-ovary-syndrome-pcos[↩][↩]

- He, F., & Le, Y. (2020, June 17). Role of gut microbiota in the development of insulin resistance and the mechanism underlying polycystic ovary syndrome: A review. Journal of Ovarian Research. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s13048-020-00670-3[↩][↩][↩]

- Jobira, B., Frank, D. N., Pyle, L., Silveira, L. J., Kelsey, M. M., Garcia-Reyes, Y., Robertson, C. E., Ir, D., Nadeau, K. J., & Cree-Green, M. (2020). Obese Adolescents With PCOS Have Altered Biodiversity and Relative Abundance in Gastrointestinal Microbiota. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, 105(6), e2134–e2144. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgz263[↩][↩]

- Guo, Y., Qi, Y., Yang, X., Zhao, L., Wen, S., Liu, Y., & Tang, L. (2016). Association between Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Gut Microbiota. PloS one, 11(4), e0153196. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153196[↩]

- Rudnicka, E., Kunicki, M., Suchta, K., Machura, P., Grymowicz, M., & Smolarczyk, R. (2020). Inflammatory Markers in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. BioMed research international, 2020, 4092470. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4092470[↩]

- Subramanian, A., Anand, A., Adderley, N. J., Okoth, K., Toulis, K. A., Gokhale, K., Sainsbury, C., O’Reilly, M. W., Arlt, W., & Nirantharakumar, K. (2021). Increased COVID-19 infections in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a population-based study. European journal of endocrinology, 184(5), 637–645. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-20-1163[↩]

- Norton Heathcare. (2021, September 13). PCOS and insulin resistance: How diet and lifestyle changes may restore balance. https://nortonhealthcare.com/news/pcos-insulin-resistance-diet/[↩]

- Woodward, A., Klonizakis, M., & Broom, D. (2020). Exercise and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 1228, 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1792-1_8[↩]