Briefing you on the latest in reproductive health research

TL/DR: This month’s roundup of period & health research updates includes: An exciting study that goes over years of an amazing trove of menstrual data; the results of following premature and near-premature infants into adulthood; and some encouraging news on pregnancy outcomes during COVID-19 from two sites.

Connecting the dots: Menstrual cycle characteristics, Type II Diabetes, and you

Menstrual research is finally beginning to get the attention it deserves, and this study is definitely worth a look.

The Nurses Health Study II is a longitudinal study that enrolled over 75,000 female-identified participants from the United States. Researchers followed these participants from 1993 to 2017 (25 years!), collecting data on menstrual cycle characteristics as well as other health factors. The aim of this particular study was to assess whether there is a direct link between irregular menstrual cycles and risk of developing type II diabetes.

If you’re an avid Fornix reader, you may already have perused our Ultimate Guide to Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). If you missed it, no worries: The guide discusses how PCOS develops, the signs and symptoms of this condition, and ways to deal.

Here’s the main takeaway as it relates to this research: For people with PCOS, hormonal dysregulation feeds into changes in ovulation that result in irregular menstrual cycles and/or missed periods. There are several other symptoms that come along with PCOS, including insulin resistance and weight gain. These can also be attributed to a hormonally dysregulated state.

Mini science lesson: The insulin-diabetes relationship

Without getting too far into the nitty gritty, the hormone insulin also affects other hormones, leading into a feedback loop of sorts that results in hyperinsulinemia (a fancy word for too much insulin in the blood)…and, eventually, insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is one of the central parts of type II diabetes.

As a general rule of thumb, type I diabetes is thought to be a condition where the pancreas itself doesn’t have the capacity to make enough insulin, whereas type II diabetes is some combination of the pancreas not making enough insulin and (in the classic form) widespread insulin resistance. Meaning that even when there is some insulin going out into the bloodstream, the organs that need to respond to it simply do not (at least, not at those levels). This has a series of downstream effects.

Insulin is super important for using up and absorbing glucose in the body – without it, or without it being responded to, you’ll have a chronically higher level of glucose sugars in the blood (known in medical terms as “hyperglycemia”), as well as other signs like weight gain. In simpler terms: the sugars from that cronut you just scarfed in between Zoom sessions are just floating around in the bloodstream, causing problems.

Phew, that was a lot of science. To get back to the study at hand… the researchers in this case were curious to observe this amazingly huge plethora of data about menstrual cycles over time, and answer this simple question: Is there an association between irregular or long menstrual cycles and diagnosis of type II diabetes?

Survey says…

The short answer is yes. These researchers found that women with menstrual dysfunction during their teenage years, as well as during adulthood, were more likely to develop type II diabetes than their counterparts.

To give you a sense of the numbers here, women who had self-reported irregular menstrual cycles or missing periods from the ages of 14-17 years were 32% more likely to develop type II diabetes. Women with this self-reported menstrual dysfunction from the ages of 18-22 were 41% more likely; and for women who reported this occurring from ages 29-46, this number went up to 66%. These models were adjusted for time-varying BMI and lifestyle risk factors.1

This trend was similar for longer menstrual cycles, which this study defined as a cycle length of 40 days or longer. Participants who reported having longer menstrual cycles when they were 18-22 were 37% more likely to develop type II diabetes, and if they had longer cycles in the 29-46 year time span, they were 50% more likely to develop type II diabetes.1

There was also an additive effect with irregular/long menstrual cycles and weight, inactivity, and low-quality diet, respectively. This means that your weight, how much you exercise, and what type of food you eat on the daily can affect your risk for diabetes down the road.

It is important to qualify all of this by saying that these findings are macro-level conclusions… meaning they may not be exactly applicable for every person or for every situation. In other words, don’t freak out if you happen to have an irregular cycle.

However, it is helpful to be well-versed on the data for your own knowledge and health planning purposes. Especially if you have had an irregular cycle regularly (tongue twister there, basically meaning that you don’t have the same period length each month, or that it doesn’t come every month), and that this has been going on for a significant amount of time for you, then it may be something to bring up with a provider.

In general, we can all stand to improve our diet and exercise habits over time, whether for preventing diabetes and other chronic illnesses later down the road, or just feeling more centered in our own bodies. Avoiding processed food, reducing red meat, and exercising daily or every other day are all habits that can make us feel healthier from the inside out.

Preemies and near-preemies: Where are they now?

In other news, there’s new data out about how preterm and early term infants do later on in adulthood. Drawing from Nordic birth cohorts, these researchers followed up with over 6M individuals to see what their health outcomes were over time.2

For background, infants that are born prematurely often have health issues early on in life, as their lungs haven’t had the time to fully develop in-utero. However, there hasn’t been much literature published on how these babies do much later on in life, like in their 20s or further into adulthood.

This is important because, if we have more information on how these babies do later on in life, then researchers and physicians can think about ways to prevent problems through medication or other interventions. This study is one of the largest study populations to examine this question, which is very exciting from a data analysis perspective.

In sum, the study found that adults that were born pre-term or early term were at an increased risk of death compared to the control group (e.g., adults born at least to term).2 FYI, this was all-cause death as well as deaths due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs are sometimes referred to as chronic diseases, and include things like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, and cancer.

This effect was also stronger in female-identified study participants, a concerning finding. The authors do mention that socio-economic factors, as well as maternal factors, could help to explain these findings – but these were also accounted for in the analysis. This goes to show that there are still vast gaps in outcomes between premature/close-to-term infants and to-term infants, even later on in life.

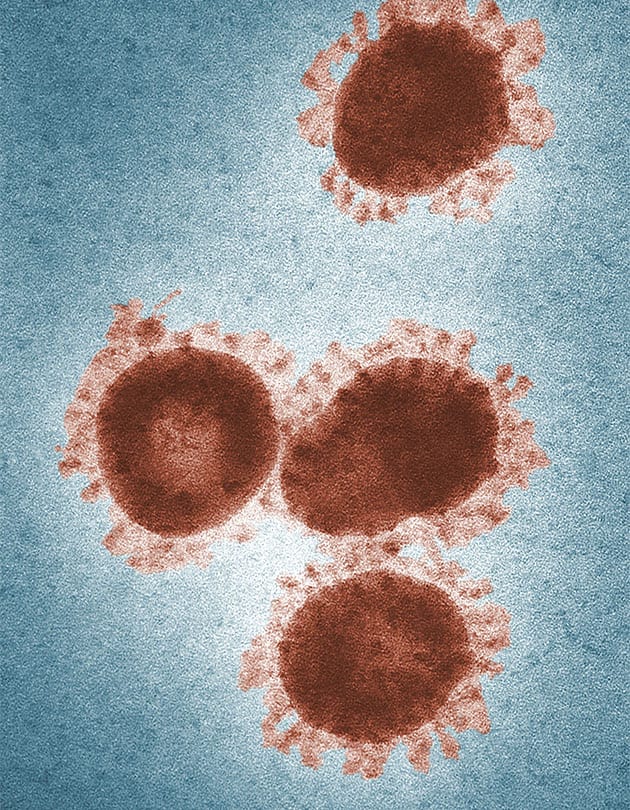

Pregnancy during COVID-19: New data on stillbirths in the U.S. and U.K.

This pandemic has been indescribably difficult for all of us, and this, of course, holds true for pregnant people. Expecting parents have faced many changes over the course of the past year, especially in seeking and accessing care during this challenging time.

Researchers have sought to understand how pregnant people are receiving healthcare throughout the pandemic – as well as the results of those pregnancies. Two recent studies have provided some encouraging data, sharing results from their hospitals in Philadelphia, PA and the U.K., respectively.

The authors of the Philadelphia study write that, “this study did not detect significant changes in preterm or stillbirth rates during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in a racially diverse urban cohort from two Philadelphia hospitals. Although these data allow for disaggregation of spontaneous and medically indicated preterm births, no differences in overall rates of these phenotypes were detected.”3

To translate, this means that not only was there no significant difference in the number of preterm or stillbirth rates in this hospital — but also that this held true even taking into account medical reasons that a pregnant person may need to prematurely deliver.

The U.K. study also found reassuring data, noting that “there was no evidence of any increase in stillbirths regionally or nationally during the COVID-19 pandemic in England when compared with the same months in the previous year and despite variable community SARS-CoV-2 incidence rates in different regions.”4

These are, of course, only two data points to a much larger, complex issue, and the outcomes of pregnancy during the pandemic should continue to be explored, both in terms of research as well as patient experiences.

This article is informational only and is not offered as medical advice, nor does it substitute for a consultation with your physician. If you have any gynecological/medical concerns or conditions, please consult your physician.

© 2021 The Flex Company. All Rights Reserved.