IN THIS ARTICLE

Is there such thing as normal vaginal pH?

TL/DR: The term “vaginal pH balance” refers to the relative acidity or alkalinity of your vaginal flora. Healthy vaginal pH levels range from 3.5 to 4.5, but your “normal” can change with time and age. When your pH balance levels increase suddenly, bacteria and yeast are more easily able to survive in the vaginal canal. This creates lots of unpleasant symptoms, like itching, burning, and odor, and can even cause an infection.

pH balance. It’s a term we see thrown around all the time in reference to vaginas. You’ve probably encountered “pH-balanced” intimate wash, wipes, and lube at the drugstore. Maybe you came across supplements that claim to support “healthy pH” for women. But what does this term actually mean, and why is it important?

Sure, you might recall from your high school chemistry class that pH measures the acidity of a substance – or maybe you worked at your neighborhood swimming pool and remember using pH test strips to test and balance the water. Turns out, your doctor or OB-GYN might use similar strips to test your vaginal pH.

Curious about what vaginal pH is and how it affects your overall health? Read on to learn more about this mysterious indicator of vaginal wellbeing. We’ll cover how to test it and what to do if you’re experiencing symptoms like itching, burning, or abnormal vaginal discharge.

First things first: What is pH?

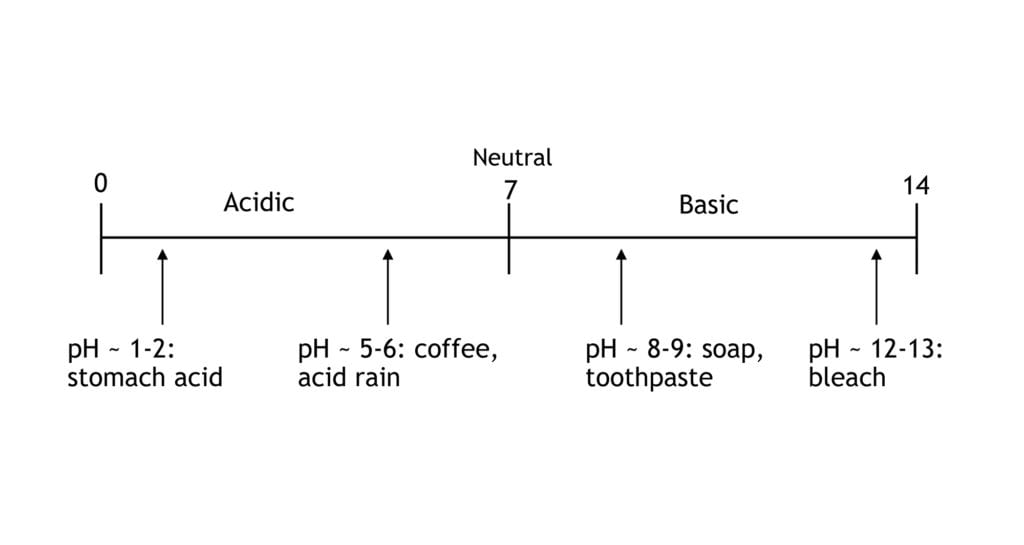

pH level is a measurement of how acidic or alkaline a substance is. You can measure the pH of pretty much anything: water, grape juice, battery acid, urine… you name it. Every substance will have a pH that falls somewhere along the pH scale, which goes from 1 to 14.

If it measures low on the scale (pH1), it means the substance is very acidic. If it measures high on the scale (pH7), the substance is very alkaline.

You’re probably pretty familiar with acids: Citrus, like lemon juice, is acidic. You may be less familiar with alkaline things, but these tend to be soapy substances. Think baking soda or liquid drain cleaner. pH7 (right at the middle of the scale) is completely neutral – neither acidic or alkaline – like pure, distilled water.

So, pH is all about acidity, or the lack thereof. But what is it, really? In scientific terms, pH is just a measure of the relative amount of free hydrogen and hydroxyl ions in the water. A substance that has more free hydrogen ions is acidic, whereas a substance that has more free hydroxyl ions is basic.

What does pH have to do with your vagina?

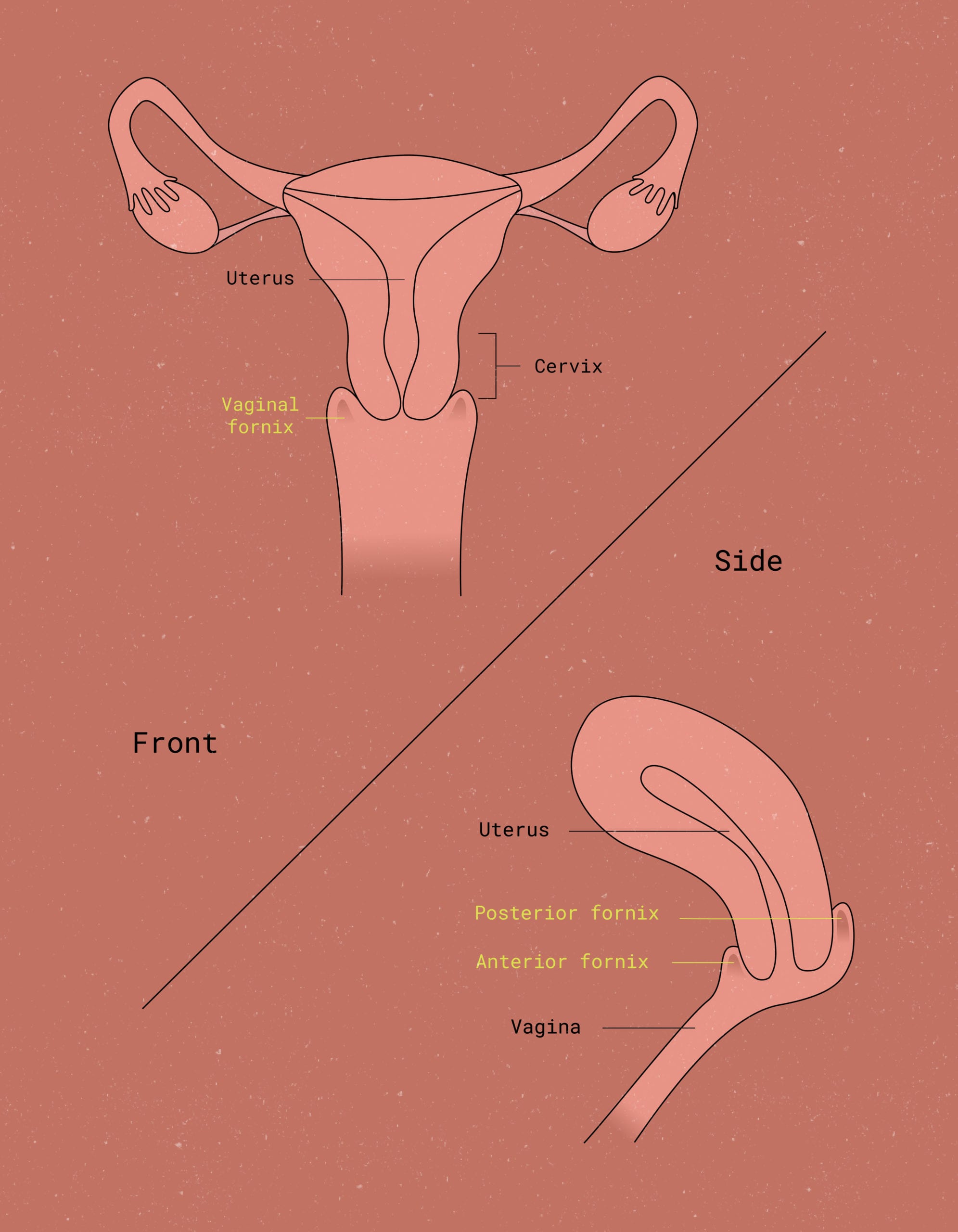

As most vagina-owners are well aware, the vagina has a lot of fluid. This is most often evidenced by the discharge that sometimes pays a surprise visit to our underwear.

Vaginal fluid is made up of a whole bunch of different substances. These substances include cells shed by the cervix and vaginal walls, bacteria, water, mucus, electrolytes, and proteins (i.e. secretory immunoglobulin A).1 Some of the bacteria is “good” bacteria, like Lactobacilli.2 All together, you have your magical and wonderful vaginal secretions, working to keep your vagina clean and your reproductive system healthy.

Like all other bodily fluids, your vaginal secretions (and internal vaginal ecosystem) have a particular acidity level. This level can fluctuate day by day as the result of a LOT of different factors.

A “normal” vaginal pH level is, in general, between 3.5 and 4.5.3 However, your normal may not be the same as someone else’s normal, and your “baseline” often changes as you age.

Let’s revisit that number for a sec. pH 3.8 is pretty acidic! It’s on par with apple or orange juice. Apple juice has an approximate pH of between 3.35 and 4; orange juice ranges from 3.3 to 4.2.

Researchers have speculated that the acidity of vaginal secretions is by design. We’ll spare you the technicalities, but the general gist is this:

Most “bad” bacteria (the kind that causes bacterial infections) cannot thrive in an acidic environment. Acidic vaginal secretions, therefore, help prevent pathogenic microorganisms from running amuck. When out of control, they can cause infections that make their way into the cervix or uterus. Such infections, especially prior to modern medicine, could be deadly.

The vagina needs to be acidic enough that it maintains its antiseptic qualities. Still, it cannot be so acidic that it kills off sperm when you’re trying to get pregnant.

How does the vagina stay acidic & maintain a healthy pH?

Remember that “good” bacteria we mention above, Lactobacillus? It’s a microbe that actually helps keep the vagina in its acidic, healthy state. It does so by producing lactic acid as a byproduct of its glucose (or glycogen) metabolism.

In simpler terms? Lactobacilli eat glycogen, digest it, and poop it out as lactic acid.

So, theoretically, the more glycogen you have to feed the Lactobacilli, the more lactic acid is produced. This leads to a lower (and healthier) vaginal pH. Keep in mind that this assumption is hugely oversimplified. There’s still so much that the medical community doesn’t know or fully understand about vaginal microbiota.

Not all vaginas are colonized with Lactobacilli, some have colonies of other, similar acid-producing bacteria. Some of these include Atopobium, Megasphaera, and/or Leptotrichia.2 But Lactobacillus-produced lactic acid is the most widely accepted, studied, and discussed vaginal “acidifier.”

Let’s circle back to the glycogen, the food source for the Lactobacilli. Glycogen is produced by your vaginal and cervical epithelial cells.3 The amount of glycogen present in your vaginal “ecosystem” varies widely from person to person.

Before puberty and after menopause, glycogen tends to be low. This means you’ll probably have less lactic acid in your vagina and thus a higher pH during those stages.

Some researchers have hypothesized that levels of the hormone estrogen, when elevated, increase the amount of glycogen deposited in the vagina.4 Newer studies, however, haven’t been able to confirm this correlation. 3

There’s still a lot of ongoing debate about what affects glycogen levels. Including what role estrogen or progesterone have – if any, and why it varies so much across individuals. We’ll keep you updated as we learn more!

What happens when your vaginal pH is off-balance?

When the pH level of your vagina increase to 4.5 or higher, it becomes less acidic. At this point, your vagina starts to look like a more appealing home for things like harmful bacteria or parasites. This is when you start experiencing symptoms of unbalanced pH levels, such as: vaginal odor, discomfort, and infections.

All microorganisms prefer a neutral pH for optimum growth. However, some bacteria can still survive and grow in more acidic values. This is the case of the Lactobacilli that help keep your vagina acidic.

Most unhealthy microorganisms, however, stop growing at a pH of around 5.0. So it makes sense that a lower pH is generally better for your vagina.

BACTERIAL VAGINOSIS

When your vaginal pH is too high, populations of unhealthy anaerobic bacteria tend to increase. These bacteria include Gardnerella vaginalis and Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus, and Bacteroides – don’t worry, we have no idea how to pronounce them, either. These are the bacteria that most commonly cause bacterial vaginosis, a.k.a. BV – the most common type of vaginal infection among uterus-havers of childbearing age.5

Symptoms of BV are similar to those of a yeast infection – itching, burning, and a funky smell. However, its signature flourish is thin, grayish vaginal discharge. The odor is notably fishy and the infection may also cause pain or a burning sensation during urination.6

If you think you may have BV, give your healthcare provider a call. Sometimes, it’ll go away on its own, but your doctor may also prescribe antibiotics for a persistent case.

TRICHOMONIASIS

A too-high vaginal pH may also make you more susceptible to trichomoniasis (“trich”). Trichomoniasis is an STI caused by a tiny parasite called vaginalis trichomonas. Like the other microscopic intruders that cause BV, trichomonas survives more easily in alkaline environments. Studies have found a strong link between vaginal microflora with high proportions of anaerobes and instances of trichomoniasis.7

BV is not necessarily sexually transmitted. But it is a fact that healthy sperm can increase vaginal pH and thus, increase the risk for BV. Trichomoniasis in the other hand, is only transmitted through sex (penis + vagina or vagina + vagina, according to the CDC).

If you’ve had it, you’re not alone, Trichomoniasis is the most common and is also easily treatable. Treament options include metronidazole or tinidazole, both of which are oral antibiotics.8

Keep in mind that, for 70% of infected individuals, trich causes no symptoms. Another reason to get tested regularly if you’re having unprotected sex (no shade!). Those who do experience symptoms usually report itching, buring, pain during urination, or a change in vaginal discharge.

Keep in mind that having trich does increase your risk for contracting other STIs like HIV. So, it’s a good idea to get treated right away if you test positive.8

CAN VAGINAL pH GO TOO LOW?

Good question! It’s unlikely. Unless you’re sticking a highly acidic substance up there, like apple cider vinegar, which is definitely a bad idea.

If your vaginal pH is unusually low after testing it, keep in mind that it could impact your fertility. Too acidic, and sperm have a much lower chance of survival! Talk to your healthcare provider to learn more.

Vaginal pH & yeast infections

Contrary to popular belief, there’s no direct, proven correlation between vaginal pH and yeast infections. Several studies have been published on the subject. However, none have found that a more acidic vaginal microbiome inhibits the ability of Candida albicans to survive.9 10

C. albicans and its cousin, C. glabrata, which can also cause yeast infections. These are pretty tough species and they can resist treatment. They often pops right back up if even a handful of survivors hang in there after your latest round of Monistat. That’s why vaginal yeast infections can be so annoyingly persistent.

If you get lots of yeast infections, don’t assume your vaginal pH is off balance! Talk to your doctor to get a better idea of what the root cause might be.

What affects vaginal pH balance?

Things that can affect your vaginal pH balance include but aren’t limited to:

Antibiotics.

If you’re taking antibiotics, they might not just be killing the unhealthy bacteria they were prescribed for. They can actually end up wiping out some of that good bacteria in your vagina, the lactobacilli.

If you’re on antibiotics for something non-vagina-related, remember to balance your system out by ingesting more probiotic foods. Cultured yogurt (not the sugary kind), kefir, kimchi, and sauerkraut all contain lots of probiotics. This is the healthy bacteria your body needs to maintain a healthy gut and vaginal microbiome.

You can also take probiotics in pill form, but ask your doctor for a recommendation: Not all brands are created equal! The best probiotic supplements tend to be the ones that require refrigeration and that have a shorter expiration period (it means they’re fresher and more effective).

Your menstruation.

Yup, another reason to strongly dislike your period: It can screw up your vaginal pH balance. This is because blood has a pH of 7.4, a whole lot higher than your vagina’s “neutral” state. When you menstruate, your vagina’s pH levels increase up to an average of 6.6 on cycle day 2, according to one study.11

Menstrual hygiene products may also impact the vaginal microbiota. This is true, especially for products that absorb rather than collect mensesAnother term for menstrual flow (commonly known as your period)., like tampons. These products hold blood inside your vagina for longer than your body intended, further disrupting the pH balance of your vagina and encouraging the growth of bacteria.

This is part of why it’s so important to change tampons every 4-8 hours. Menstrual blood naturally contains a certain amount of “bad” bacteria; normally, it’s shed from the body right away. If menstrual blood stays within the vagina for too long, it may start to release higher quantities of toxins. These toxins can cause Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS).12

Avoid bacterial infections by changing your tampon frequently. You can also choose alternative period products. Consider switching to a menstrual cup or menstrual disc) made from materials that are biologically inert, like medical-grade silicone or polymers. Keep in mind that even menstrual cups and discs should be changed as often as recommended by the manufacturer.

Hormonal fluctuations.

Remember how your vagina stays acidic? That it has to do with lactobacilli, and the food source for the lactobacilli – glycogen?

Well, we still don’t know exactly how hormonal fluctuations impact glycogen production. We know there’s a definite correlation between estrogen and lactic acid (the byproduct of the lactobacilli’s consumption of glycogen).4

We do know that hormonal fluctuations impact vaginal pH balance by changing certain conditions within the vagina. Some of these conditions include the amount and viscosity of vaginal secretions. Also included are the glycogen content, and the vaginal oxygen carbon dioxide levels. We also know that lower estrogen usually correlates with an increase in vaginal pH.13

Estrogen levels change throughout your menstrual cycle. They peak right around ovulation and then drop off during the luteal phase, before your period. However, estrogen can be influenced by a number of other factors, including menopause, pregnancy, prolonged stress, and certain health conditions. So, if your balance is out of whack, it could have something to do with hormonal changes.

Douching or deodorizing.

As we mentioned before, your vagina is a smarty. It can self-clean and doesn’t need to be douched, cleansed with scented or deodorizing soaps, or “sterilized” with anything.

Rinsing with water should be enough. If you insist on washing up, choose an all-natural, mild cleanser that is diluted with water and OB-GYN-approved.

In short: Avoid douches and never put any substances up your vagina without consulting your provider, first. Otherwise, you’ll just end up killing off all those valuable, hard-working lactobacilli. You will then have to suffer through an itchy, smelly case of bacterial vaginosis as a result.

Semen.

Penis-in-vagina (PIV) sex that ends with ejaculation is another common cause of vaginal pH imbalance. According to the World Health Organization, the typical pH of liquefied semen is between 7.2 and 8.0.14 This is significantly higher than your vagina’s average pH of 3.5 to 4.5.

So, it makes sense that introducing alkaline sperm to your acidic vaginal environment tends to throw off balance, though usually only temporarily. To avoid bacterial overgrowth from the elevated pH after PIV sex, use condoms. You can also take a shower and/or pee after your partner finishes, and let gravity do its thing.

Falling asleep right after sex means sperm stays in there longer, so it’s not a bad idea to move around a bit after sex. Before passing out, you can even utilize one of the new-fangled semen-remover devices, like this sponge from Awkward Essentials.

How to test vaginal pH levels

There are two ways to test your vaginal pH. At home or at a healthcare facility, like your OB-GYN’s office.

An at-home vaginal pH test kit is, in most cases, just as reliable as the ones you’d get done with a provider. They’re relatively inexpensive and easy to use. Just search on Amazon or stop by your local drugstore. Even Monistat makes a “Vaginal Health Test” that measures your pH levels.

How do you know if your pH balance is off and when to talk to your provider

If you experience any of the symptoms below, it’s a good indicator that there’s an imbalance. Give your healthcare provider a ring to figure out what’s going on if you’re suffering from:

- Itching

- Burning sensation

- Inflammation or swelling

- Abnormal odor (fishy, cheesy)

- Unusual discharge (greenish, grayish, chunky, watery)

- Pain with urination

- Pain with sex

Key takeaways

Hopefully, by now, you have a better idea of what vaginal pH balance is and what affects it. Here’s a quick recap of everything you need to know:

- Normal vaginal pH is typically between 3.5 and 4.5. This puts it on the acidic side of the scale (where pH 7 is neutral, like water)

- The main reason your vagina stays acidic is due to the presence of “good” bacteria called lactobacilli. This bacteria will eat glycogen (secreted by your vaginal walls), digest it, and poop it out as lactic acid

- When your vaginal pH gets too high (i.e. too alkaline), your risk of infection, such as bacterial vaginosis (BV) or trichomoniasis (an STI), increases

- There are many possible triggers for pH imbalance, like taking antibiotics, being on your period, or hormonal fluctuations. We can also include pregnancy, douching or deodorizing, and the presence of semen inside the vagina

- Talk to your provider if you are experiencing any itching, burning, or swelling around the vagina or labia. Additionally, don’t forget to report any unusual odor or discharge, or pain during sex or urination. These could be signs of a bacterial infection (partly resulting from imbalanced vaginal pH)

How to fix your pH balance

Want to learn more about how to balance your vaginal pH (or maintain a healthy balance) on your own? We have a new post dedicated to the topic coming soon: Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out!

This article is informational only and is not offered as medical advice, nor does it substitute for a consultation with your physician. If you have any gynecological/medical concerns or conditions, please consult your physician.

© 2025 The Flex Company. All Rights Reserved.

- Jr., J. E., Murray, M. T., & Joiner-Bey, H. (2016). Vaginitis. In The clinician’s handbook of natural medicine (pp. 945-959). Elsevier Health Sciences. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780702055140000877[↩]

- Linhares, I. M., Summers, P. R., Larsen, B., Giraldo, P. C., & Witkin, S. S. (2011). Contemporary perspectives on vaginal pH and lactobacilli. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 204(2), 120.e1-120.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.07.010[↩][↩]

- Mirmonsef, P., Hotton, A. L., Gilbert, D., Gioia, C. J., Maric, D., Hope, T. J., Landay, A. L., & Spear, G. T. (2016). Glycogen Levels in Undiluted Genital Fluid and Their Relationship to Vaginal pH, Estrogen, and Progesterone. PloS One, 11(4), e0153553. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153553[↩][↩][↩]

- Boskey, E., Cone, R., Whaley, K., & Moench, T. (2001). Origins of vaginal acidity: High D/L lactate ratio is consistent with bacteria being the primary source. Human Reproduction, 16(9), 1809-1813. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/16.9.1809[↩][↩]

- Turovskiy, Y., Sutyak Noll, K., & Chikindas, M. L. (2011). The aetiology of bacterial vaginosis. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 110(5), 1105–1128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.04977.x[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, February 10). STD facts – Bacterial vaginosis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/bv/stdfact-bacterial-vaginosis.htm[↩]

- Brotman, R. M., Bradford, L. L., Conrad, M., Gajer, P., Ault, K., Peralta, L., Forney, L. J., Carlton, J. M., Abdo, Z., & Ravel, J. (2012). Association between Trichomonas vaginalis and vaginal bacterial community composition among reproductive-age women. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 39(10), 807–812. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182631c79[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020, August 5). STD facts – Trichomoniasis. https://www.cdc.gov/std/trichomonas/stdfact-trichomoniasis.htm[↩][↩]

- Lourenço, A., Pedro, N. A., Salazar, S. B., & Mira, N. P. (2019). Effect of acetic acid and lactic acid at low pH in growth and Azole resistance of candida albicans and candida glabrata. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03265[↩]

- Moosa, M. S., Sobel, J. D., Elhalis, H., Du, W., & Akins, R. A. (2003). Fungicidal activity of fluconazole against candida albicans in a synthetic vagina-simulative medium. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 48(1), 161-167. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.48.1.161-167.2004[↩]

- Wagner, G., & Ottesen, B. (1982). Vaginal physiology during menstruation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 96(6 Pt 2), 921–923. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-96-6-921[↩]

- Mayo Clinic. (2020, March 18). Toxic shock syndrome – Symptoms and causes. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/toxic-shock-syndrome/symptoms-causes/syc-20355384[↩]

- Godha, K., Tucker, K. M., Biehl, C., Archer, D. F., & Mirkin, S. (2017). Human vaginal pH and microbiota: an update. Gynecological Endocrinology, 34(6), 451–455. doi:10.1080/09513590.2017.1407753[↩]

- Haugen, T. B., & Grotmol, T. (1998). pH of human semen. International Journal of Andrology, 21(2), 105–108. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2605.1998.00108.x[↩]