What is free bleeding, really?

When we think about leaking from our periods, it may conjure up embarrassing memories. Think of eighth-grade gym class when someone pointed and gawked at the circle of blood on our pants.

There’s no denying it: We grew up conditioned to feel a lot of shame around our periods. From tucking tampons into our sleeves, to using language like “time of the month” or “code red” to conceal the experience.

But what if there was a way to embrace the menstrual cycle? What if we could make periods a less hidden experience after we’ve been taught to conceal them for so long? Enter free bleeding.

Free bleeding is the refusal to use period products to collect menstrual blood.1 There are multiple reasons why menstruators might partake, ranging from personal benefits to displays of political activism and challenging societal taboos.

Here at Flex®, our mission is to help people with periods thrive. Whether that means finding a period product that works better for you or ditching period products altogether, we’re for it. For many, free bleeding is an excellent option in the “period toolkit”. How public you choose to take it is entirely up to you.

Curious about free bleeding and how it all started? Here’s what you need to know.

The movement that reignited at the 2015 London Marathon

Kiran Gandhi made history in 2015 by running the London Marathon without a tampon while on her period. Her photograph finishing the marathon with blood-soaked leggings became an iconic image for menstrual activism and the free bleeding movement. In a piece she originally published on Medium, Gandhi explains what prompted her decision and how her personal choice turned political:

“As I ran, I thought to myself about how women and men have both been effectively socialized to pretend periods don’t exist. By establishing a norm of period-shaming, [male-preferring] societies effectively prevent the ability to bond over an experience that 50% of us in the human population share monthly. By making it difficult to speak about, we don’t have language to express pain in the workplace, and we don’t acknowledge differences between women and men that must be recognized and established as acceptable norms.”

Because it is all kept quiet, women are socialized not to complain or talk about their own bodily functions, since no one can see it happening.

—Kiran Gandhi

At first, Gandhi chose to free-bleed because the idea of running the 26.2 miles with a menstrual product sounded impractical. She considered using a tampon, but was worried about chafing and discomfort. So she left her period products at home.

Gandhi’s decision to free bleed expanded from a matter of personal comfort to an homage to bleeders without access to tampons. It was also a revolt against the societal norms of keeping periods hidden—both in speech and in view.

The free bleeding movement gained notoriety in the 2010s due to Gandhi and other artists and activists.

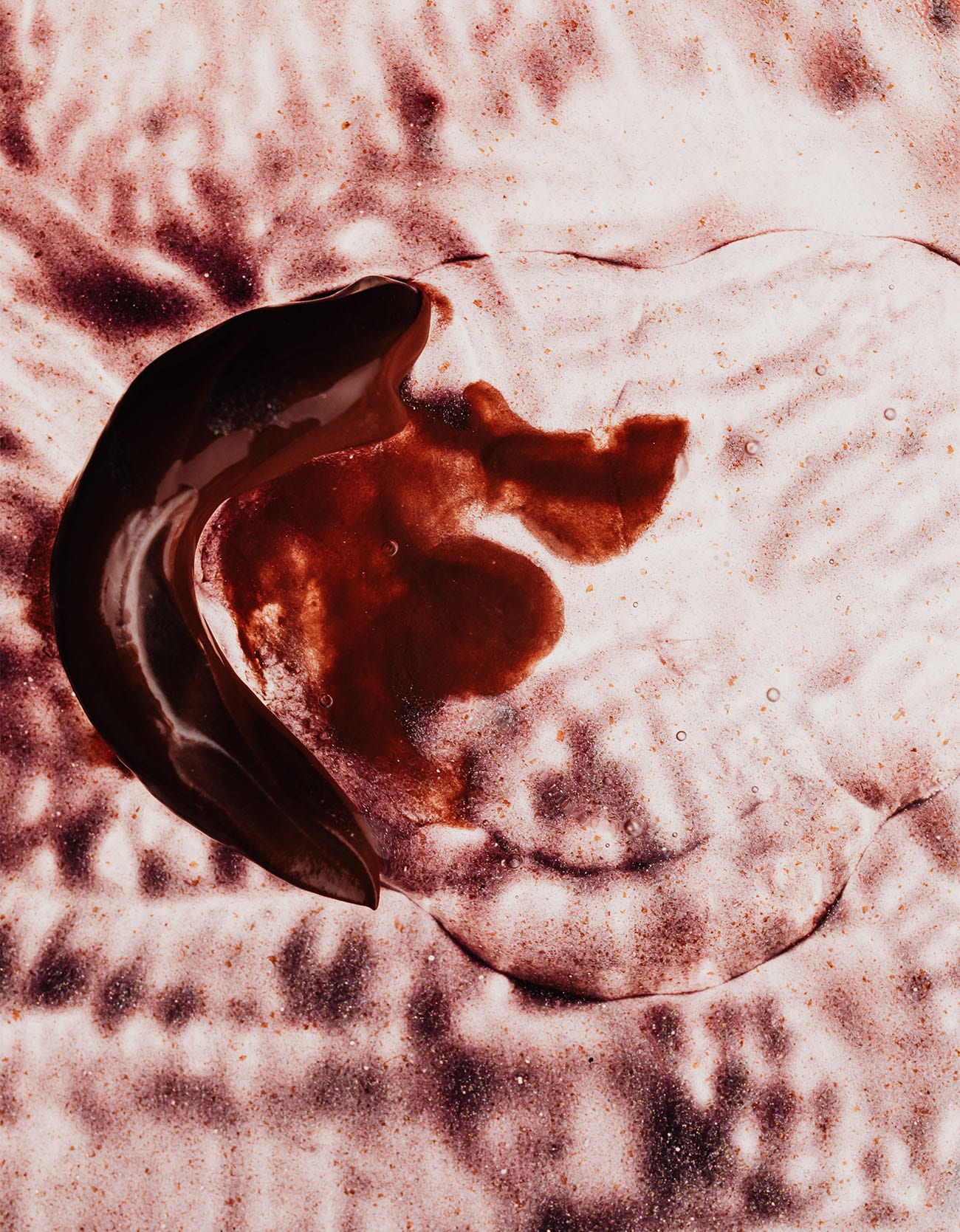

In March 2015, artist Rupi Kaur’s photographic series on period blood was shared on Instagram. The images were initially removed for violating community guidelines but were reinstated shortly after. This event brought attention to the free bleeding and period de-stigmatization movement.

Free bleeding, a movement rooted in 1970s activism, challenges societal taboos by displaying menstrual blood in art. But why is this considered radical? To understand, we need to explore decades of modern and pre-modern history.

The meaning behind free bleeding

Seeing menstrual blood out in the open tends to elicit a strong response from the public. This is because period blood has long been concealed from the public eye, as if it is somehow infectious or demonic. Menstruators are taught from a young age to feel shame about periods and their reproductive body parts.

This is not a recent phenomenon. Menstrual taboos and rituals predate even language itself. We see evidence of this in the first written text that mentions menstruation, a Latin encyclopedia published in 73 AD:

“Contact with [menstrual blood] turns new wine sour, crops touched by it become barren, grafts die, seed in gardens are dried up, the fruit of trees fall off, the edge of steel and the gleam of ivory are dulled, hives of bees die, even bronze and iron are at once seized by rust, and a horrible smell fills the air; to taste it drives dogs mad and infects their bites with an incurable poison.” 2

There are countless historical texts in which periods are regarded as “foul,” “toxic,” or “disease-causing.” Many of these were published long before modern medicine, when our understanding of hygiene, bodily fluids and disease was still rudimentary. Some scholars have argued that period stigma originated from a more basic human fear of blood.

But now that we know better, why do we continue to perpetuate the shame and stigma around menstrual bleeding? It’s a perfectly normal and healthy bodily function experienced by half of the world’s population. There is nothing “dirty” or “toxic” about menstrual blood.

As Dr. Jen Gunter writes in a 2017 blog post, “Menstrual blood is the lining of the uterus (endometrium) that leaves the body when an embryo fails to implant. If there is no pregnancy, the corpus luteum runs out of progesterone and this withdrawal of progesterone destabilizes the lining of the uterus and the blood comes out. If menstrual blood were toxic, that means human embryos are deposited in a toxic wasteland. That would be a design flaw.”

Gunter wrote the post in response to misinformation being spread on social media. The false claims, originated from a group of vegan “health” bloggers, stated that periods were toxic and promoted extreme dieting to stop menstruation.

Having a regular period is an important indicator of overall health. As such, the ACOG has lobbied for the recognition of menstruation as a fifth vital sign. 3

Despite all this, menstrual taboos persist. Think about the most recent TV commercial for pads or tampons – the liquid used to demonstrate absorption is often depicted as a blue chemical, rather than red or brown like actual menstrual blood.

How can we challenge stigma and normalize menstruation when we offer a false depiction of what periods look like?

Even actress and comedian Whitney Cummings has admitted that, as a child, she had thoroughly believed that period blood was blue. As recorded in an article for Shape magazine, Cummings “expected blue liquid to come out of her vagina during her first period, since that’s what was used in Maxi Pad commercials. Unsurprisingly, she thought the blood that actually appeared on the pad meant she was dying.”

Free bleeding catalyzes important conversations around menstruation and reproductive health more broadly. It’s not just about pushing for societal recognition of periods as normal and healthy. It is also a matter of drawing attention to larger issues like period poverty, sustainability, gender equality, and sex education.

To be or not to be a free bleeder?

Are you free bleeding-curious? Even if you’re not, that’s totally okay!

There are many reasons why someone might choose to stop using period products. For some, it’s political. For others, it’s personal.

Some of the physical health benefits of free bleeding include increased comfort and a possible reduction in cramping. Free bleeding also reduces the risk for infection or Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS). Leaving a tampon or menstrual cup inserted for too long can cause TSS.

In a piece written for Vice magazine, Aurora Tejeida shares her experience trying free bleeding for the first time. She found that her cramps were more manageable compared to using a tampon. Despite concerns about mess, she discovered that strategic use of a towel helped prevent stains.

Tejeida sums up her free bleeding experience as follows: “If you want to feel liberated, try it one day. Not giving a f*ck is the best feeling.”

There was an enlightening feeling that came with knowing exactly when I was and wasn’t bleeding. It really made me feel more in touch with my body, even if I was sure I was bleeding through my yoga pants […] As far as I could tell, nobody was offended.

—Aurora Tejeida for Vice

She adds, “I started to think that a lot of my period habits were more micromanaging than necessary and had more to do with imagined worst-case scenarios than the actual amount of blood my body produces.”

Tejeida’s last statement may hold a universal truth, although everyone’s flow is unique. Many of us may “overdo it” when it comes to period protection due to fear of shame or embarrassment from a stain. Perhaps we anxiously change tampons, pads, or empty menstrual cups more frequently than necessary. Disposable pads and tampons could also be a contributing factor to the existing environmental issues.

So, if you’re thinking about giving free bleeding a shot, consider not only the physical and financial benefits but also the psychological impact.

Logistic cosiderations

Of course, there are certain logistical considerations to keep in mind when free bleeding (i.e. laundry, washing, not staining your brand-new couch). However, with a confident mindset and a couple of spare towels at your side, there’s nothing to fear.

We should point out that many people around the world free bleed not by choice, but out of necessity. Period poverty is a widespread phenomenon that impacts anyone who lacks the financial resources to obtain period products. Affected groups range from school-aged youth to individuals living in impoverished countries to the homeless and the incarcerated.

This adds a layer of complexity to free bleeding when done as a political act. While menstrual activism works to break down period stigma, it must also extend to help those affected by period poverty.

What counts as free bleeding, though?

If you free bleed for only part of your period, does it count? The dictionary definition of free bleeding is refusing to wear anything that collects menstrual blood. Don’t worry, there is no “free bleeding police” who will confront you for doing it wrong or not being radical enough.

We like to think of free bleeding on a spectrum. There are different “levels,” so to speak, maybe starting with period underwear as an entry point. From there, one might venture onto using only a pantyliner and, eventually, nothing at all. Maybe just keep a towel at hand, to protect furniture from stains.

Some people free bleed only on the lighter days of their period, or only while wearing dark clothing. Others might free bleed at home but use traditional period products while out and about. What’s most important to remember is that how—and why—you choose to free bleed is entirely up to you.

Does free bleeding make your period end faster?

While there is some evidence to suggest that free bleeding may speed up the end of your menstrual cycle, there is no scientific proof that this actually works.

While some free-bleeders have reported benefits like reduced cramps and fatigue, there is insufficient research to definitively say if free bleeding shortens the duration of your period.

A few tips for free-bleeding:

- To help prevent stains, put a towel down if you’re free bleeding at home or on your sheets

- Bring an extra pair of underwear when you leave the house, double on heavier days

- Start free bleeding on a lighter day to gauge the amount of blood you might lose

- Blood stains are a reality for free bleeders. Some prefer dark clothing or separate panties during menstruation.

This article is informational only and is not offered as medical advice. It is not a substitute for a consultation with your physician. If you have any gynecological/medical concerns or conditions, please consult your physician.

© 2023 The Flex Company. All Rights Reserved.

- Bobel, C., Winkler, I. T., Fahs, B., Hasson, K. A., Kissling, E. A., & Roberts, T. (2020). (In)Visible Bleeding: The Menstrual Concealment Imperative. In The palgrave handbook of critical menstruation studies (p. 331). Palgrave Macmillan.[↩]

- Murphy, T. M. (2004). Pliny the elder’s natural history: The empire in the encyclopedia.[↩]

- American College of Obstetrics & Gynecology. (2015, December). Menstruation in girls and adolescents: Using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2015/12/menstruation-in-girls-and-adolescents-using-the-menstrual-cycle-as-a-vital-sign[↩]